The Beginnings of Queer Culture in San Francisco

The Gay Capital of America

San Francisco has always been a city with a reputation for rule-breaking, costume parties and wild nightlife, back to its earliest Gold Rush days as the capital of California’s lawless “Barbary Coast.”

In the aftermath of Prohibition, gay and lesbian bars proliferated across the city. Decades before the Castro emerged as a global center of gay liberation in the 1970s, San Francisco queer culture was already flourishing in other neighborhoods, including North Beach, Nob Hill, the Tenderloin, and Haight-Ashbury. In 1964, LIFE magazine proclaimed San Francisco the “gay capital” of America.

Part of what transformed San Francisco into this space were a series of migrations. The end of prohibition, the discharge of gay soldiers into the city after WWII, the 1950s Beat Movement and the new political consciousness of the ‘60s leading to the “Summer of Love” all helped make San Francisco an important destination for queer migrants coming from other parts of the United States and across the World.

1930s: Rise of the Gay Bar

The end of Prohibition in 1933 led to a proliferation of bars and nightclubs in San Francisco, particularly in the North Beach and Telegraph Hill neighborhoods. A club called “Mona’s” was one of the most popular, and by the late 1930s it had become infamously known as the first lesbian nightclub in San Francisco. Another nightclub, Finnochio’s, became well known for nightly drag performances (then referred to as “female impersonation”) after Prohibition.

This 1945 guidebook titled Where to Sin in San Francisco advertised Mona’s as a “Boy-Girl” bar where “...many of the little girl customers look like boys'' (page 57). It also describes Finnochio’s drag shows: “wigged, gowned, rouged, lipsticked, and mascara-ed, ten beautiful boys become singing, clowning, ravishing women. In a revue of revues. It’s a Rabelousy rendezvous. It’s different!” (page 93). Popular among tourists, these kinds of guidebooks established San Francisco’s reputation for sex and gender nonconformity.

Even though alcohol was legal again, homosexuality remained illegal. Queer nightclubs became important places where LGBTQ people could gather in a time when they were otherwise forced to hide in public.

1940s: Blue Ticket to Sin City

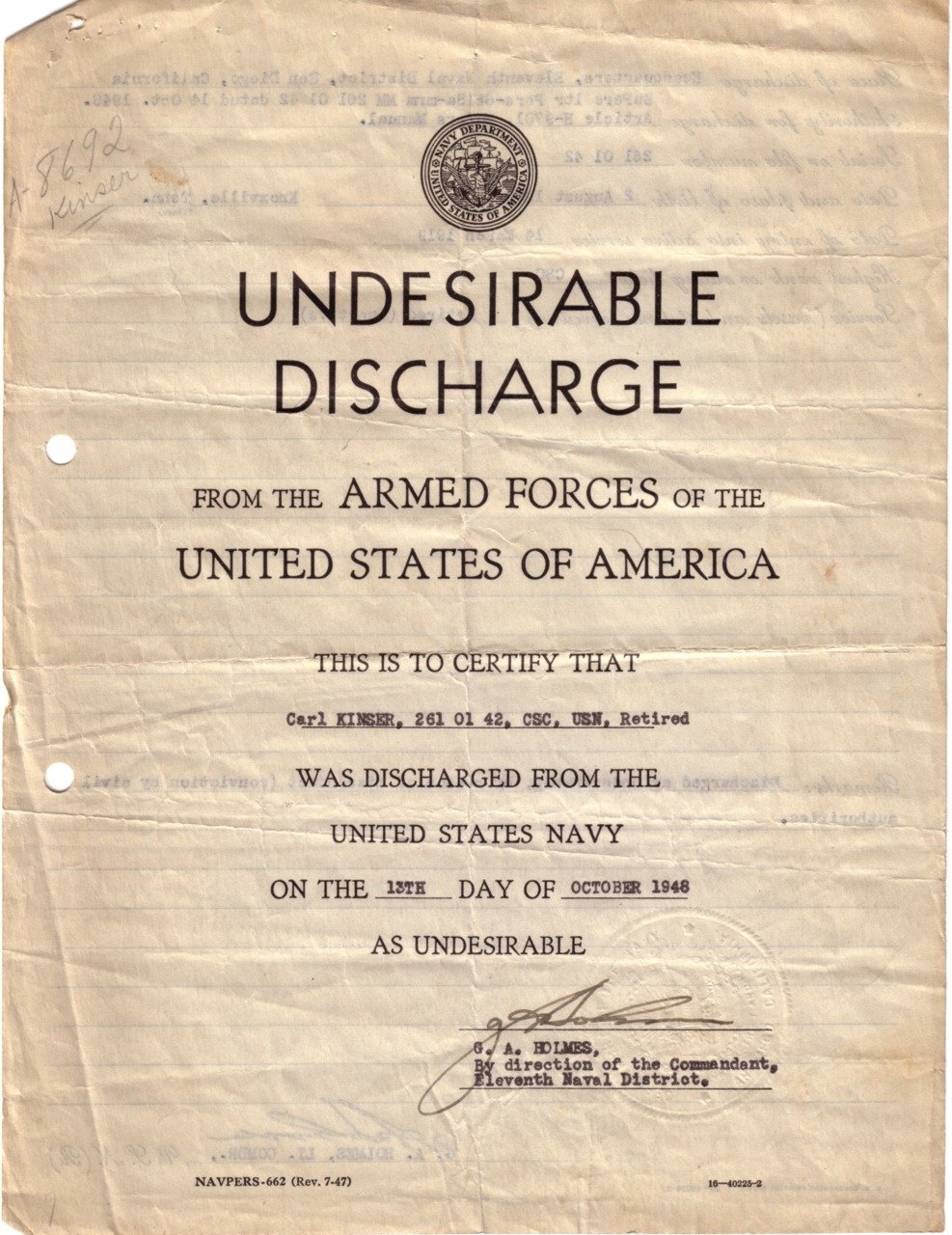

During World War II, thousands of soldiers were discharged from the military for suspected homosexual activities. These so-called “blue discharges” were public, so forced gay servicemen to come out of the closet and made it difficult for many to resume their civilian lives.

San Francisco was the major Navy port for the Pacific Ocean theater during World War II, so thousands of these soldiers were released from service in the City. Rather than returning to other parts of the country, where they might face even more stigma, many stayed in San Francisco after the war. However, military presence in the city also brought tighter regulation of queer spaces. From 1942 to 1943, military patrols known as the San Francisco Moral Drive targeted and raided the gay bars, claiming to be protecting servicemen from predatory homosexuals.

Gay GIs found camaraderie in bars but risked getting caught by the military police. The Black Cat Cafe, a notoriously gay hangout in San Francisco, was declared off limits to military personnel. In upper left, the military police stands guard to make sure only civilians enter the premises.

Credit: Black Cat: By Samuel A. Cherry

During WWII, to cut costs and save time, the military began issuing ‘blue’ discharge or ‘blue tickets’ to those who left because of “undesirable habits and traits of character.” A broad definition used against women, African Americans, and LGBTQ servicemen. 9,000 men and women received ‘blue’ discharge because of their sexuality.

Lt Harvey Milk, who would go on to become the “Mayor of Castro Street” and San Francisco’s first openly gay elected official, was “other than honorably” discharged from the Navy in 1955 after being threatened with a court martial. Until the U.S. Navy released his personnel file in 2020, the veracity of this story was long doubted, as Milk’s archival papers included what appeared to be an honorable discharge slip. Milk probably forged these papers in order to show them to prospective employers and avoid being blacklisted.

Credit: Harvey Milk Archives-Scott Smith Collection, LGBTQIA Center, San Francisco Public Library

1950s: A Bohemian Haven

In the 1950s, a counter-culture movement started to coalesce in San Francisco. Its adherents – who came to be stereotyped as Beatniks – pushed back against mainstream middle class American values, with leading Beat poets and writers like Allen Ginsburg and Jack Kerouac advocating non conformity. The Beat generation’s desire for sexual liberation fostered increasing acceptance towards homosexuality, and as the movement grew in popularity, its members helped to establishment many gay social and political groups in San Francisco. The Daughters of Bilitis, founded in 1955, was the first lesbian-centered organization in the USA, while the Mattachine Society, one of the earliest gay rights organizations in the USA, headquartered itself in San Francisco from 1956.

The 1956 publication of Alan Ginsberg’s poem Howl was a seminal moment in the Beat Movement. The poem, which explicitly references homosexuality and sodomy, launched, became the subject of an obscenity trial in 1957.

1960s: Getting Organized

The fight for gay rights in San Francisco came into full force in the 1960s. In 1961, entertainer and drag queen José Sarria became the first openly gay candidate in the USA to run for public office. The Tavern Guild was founded as the first gay business association in response to continued police raids and harassment. Jose Sarria also founded the Society for Individual Rights (SIR) in San Francisco, the first homophile organization focused on the needs of the gay community, versus their public perception from straight America.

José Sarria campaign poster, 1961. Courtesy of the GLBT Historical Society

In 1964 Life magazine published a photographic essay by Paul Welch titled “Homosexuality in America”. Read by millions, it was influential in the framing of San Francisco as the “gay capital of America”

Want to Learn More?

GLBT HIstorical Society

Wide-Open Town: A History of Queer San Francisco to 1965, Nan Alamilla Boyd

Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War II, Alan Bérubé

SF Gay History

Forging gay identities: Organizing sexuality in San Francisco, 1950-1994. Elizabeth Armstrong

CITYWIDE HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT FOR LGBTQ HISTORY IN SAN FRANCISCO, pp. 13 - 104