The Mother of Olvera Street

A Dirty Alleyway

In the early 1920s, Christine Sterling stared down a dirty alley in the heart of Los Angeles, lined with crumbling buildings. She had recently moved to L.A. from Oakland, drawn to the city’s promises of sunshine, palm trees, and the romantic Spanish influences of Southern California.

The dirty alley was Olvera Street (originally known as Wine Street). It had once been a thriving social and commercial center of wineries, adobe homes and small businesses. The adjacent plaza was the historic heart of the city, what some referred to as the “birthplace of Los Angeles.” And, although the city itself was thriving when Christine arrived in 1926, this area was clearly neglected, and falling into disrepair.

“Olvera Street at this time was not only a filthy alley but was a crime hole of the worst description…bootleggers, white slave operators, dope peddlers all had headquarters and hiding places on the street.” —Christine Sterling

Prohibition had left the winery in the Pelanconi House—the oldest brick building in the city— mostly out of business. The Pico Pico House, built by the last Mexican governor in California, was dirty and falling apart. Short term boarders and sex workers had taken up in the once grand Victorian-style Sepulveda House. Amidst the ruin, Christine’s biggest disappointment was a low, whitewashed building, with dark wood trim and a wraparound porch: the Avila Adobe.

“Today I stood in the silent rooms, saw the crumbling walls, the boarded-up windows, the dirt and neglect. I remember taking from the public library a book on the “History of Los Angeles.” It was a picture of this old house labeled “American headquarters in 1847.” I walked out into the patio. The fine old pepper trees were now just barren stumps. A pile of rotting garbage replaced the flowers which once blossomed there. But in spite of it all, the spirit of those men and women who lived and loved here in this old home still lingered about the place.”—Christine Sterling

The Avila Adobe, circa 1920s. Courtesy of the El Pueblo Historic Monument

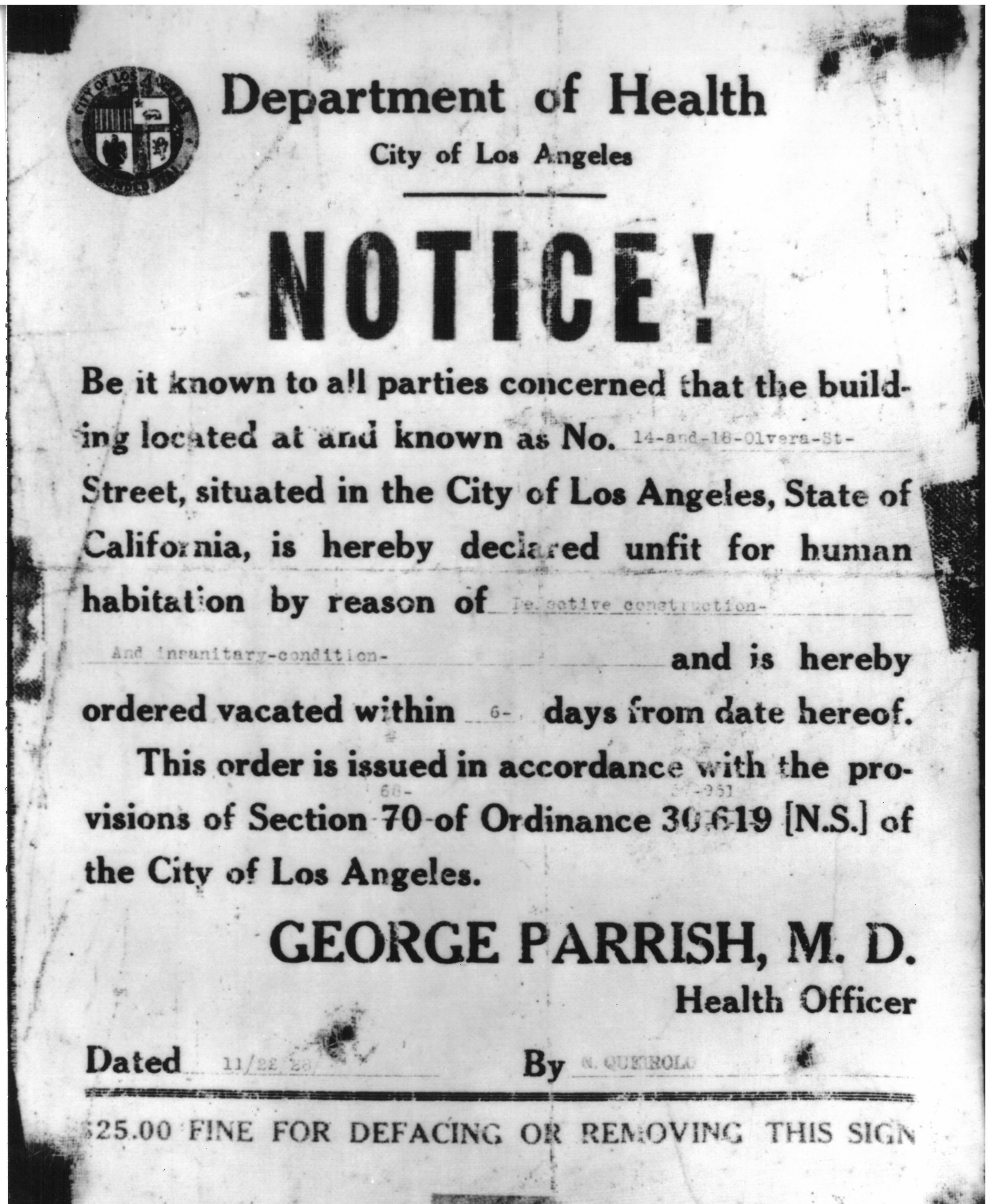

The Department of Health’s posted condemnation notice of the Avila Adobe. Courtesy El Pueblo Monument

When Christine found it in 1926, the city had scheduled the Avila Adobe for demolition, and the street around it was decrepit and forgotten.

Christine was distraught over the idea that most Los Angelenos had forgotten their city’s history. But the visit to Olvera Street also lit a fire within Christine Sterling, and she began a tireless, one-woman campaign to rehabilitate the heart of old Los Angeles.

Shall We Condemn?

Christine started by petitioning city leaders, imploring them to take action to preserve L.A.’s history. She wrote to Harry Chandler, publisher of the Los Angeles Times and one of the most powerful men in the city, who agreed to cover her campaign in his paper. She pitched anyone and everyone who would agree to see her: “I called on everyone imaginable, went from office to office, chair to chair; waited long hours, alternately humiliated and encouraged.”

“Miles of conversation, but no definite, tangible results,”

Christine wrote in her diary in 1928. After two long years, phone calls and meetings weren’t getting her anywhere. So, Christine decided to pull a publicity stunt: she installed a huge, twelve foot sign in front of the Avila Adobe. Responding to the city’s posted demolition notice, it was hand-painted with the question, “SHALL WE CONDEMN?”

Christine Sterling and Harry Chandler, who became lifelong collaborators, circa 1940s. Courtesy El Pueblo Monument

Christine chose in that moment to appeal to her Anglo-American audience by emphasizing the adobe’s importance to American history, noting that Navy Commodore Robert F. Stockton, Major John C. Fremont, and Kit Carson had once quartered there during the Mexican-American War. The last sentence of her dramatic sign read, “If this old landmark is not worthy of preservation, then there is no sentiment, no patriotism, no country, no flag. Los Angeles will be forever marked a transient, orphan city if she allows her roots to rot in a soil impoverished by neglect.”

After Sterling called the local papers with an anonymous tip about the gigantic sign, her campaign, aided by Chandler’s considerable political clout, took on momentum. The city council reversed the order of condemnation, and the Rimpau family, descendants of the Avilas, gave Sterling permission to renovate the adobe.

But, while the fate of the adobe had changed, she knew it still wouldn’t get any visitors unless Olvera Street and the surrounding plaza were transformed. For a white woman of her time, she took an interesting approach to the next phase of her campaign, now highlighting the area’s pre-American history and L.A.’s Mexican population, which was over 200,000 thousand: “It might be well to take our Mexican population seriously and allow them to put a little of the romance and picturesque into our city which we so freely advertise ourselves as possessing. The plaza should be converted into a social and commercial Latin American center.”

In July 1929, Sterling hosted a fated luncheon on the patio of the adobe. Between rounds of frijoles and coffee, she pitched her idea for a Mexican-style marketplace to a group of men representing the City Council, the newspapers, and business interests. It was a major turning point. Right there, on the steps of the adobe, the Chief of police announced he would “donate” a crew of prison inmates to do the manual labor. Blue Diamond Cement and the Simons Brick Company pledged building materials. A handful of prominent businessmen put up money.

By September 1929, the city council passed an ordinance to close Olvera Street to cars and “reconstruct it as a place of historic interest.” Christine Sterling had single-handedly taken on the L.A. establishment—and won.

Opening in a “Blaze of Glory”

Work began on Olvera Street in November 1929. Christine documented the progress in her diary:

Nov. 7, 1929: “Work Started this morning on Olvera Street. With my two children, twenty-five prisoners, fifty percent protest from the property owners and a lawsuit thrown in for good measure, we can put the first pricks and shovels into the dirt of the old street…”

Nov 14: “Progress slow. The surface of the street in spots is covered with heavy oil cake and it is like cement to break the surface. About fifty dollars contributed from the general public towards tile. Weather warm.”

November 21: “One of the prisoners is a good carpenter, another an electrician. Each night I pray they will arrest a bricklayer and a plumber.”

November 24: “My prayers answered with just a slight error. Two bricklayers and no plumber.”

December 25: “Prisoners had a little Christmas party in the patio of the adobe. … In the cellar of the Pelanconi House, prisoners dug up several cases of whiskey while the guard was on the other end of the street, and a truck had to take them back to jail.”

Feb 25: “...I ordered a large cross to place at the entrance of the street. I am going to name the Street ‘El Paseo de Los Angeles’ which means The Pathway of The Angels.”

March 10: “Street work completed!...we have made little awning stands or ‘puestos’ for the street. Each one will be given to a Mexican family and they will sell all things typical of Mexico. Tourists will be interested in their wares and not only will this mean a living for the Mexican, but it will make the street picturesque and colorful. Lovely little shops and studios are being taken by American people and these will add greater interest to the whole.”

By spring, the renovation was complete. On Easter Sunday, 1930, after four long years of struggle, Christine Sterling’s dream was realized: Olvera Street opened to the public in a “blaze of glory.”

As the managing director—the “Mother of Olvera Street”—Christine personally approved each tenant, ensuring that Olvera Street always looked cheerful, colorful, and exotic-yet-safe.Colorful stalls called “puestos’ lined the newly paved street, bursting with trinkets from Mexico. She hired actors to portray campesinos (Mexican peasants) sleeping under trees. Vendors were required to wear colorful “costumes,” strumming guitars as Anglo-American tourists strolled the street.Paseo de Los Ángeles was heralded as a success in the local press: “A Mexican Street of Yesterday in the City of Today.”

Dancing in Olvera Street. Credit:Mary Evans Picture Library/Pharcide/Bridgeman Images

Credit: Los Angeles Public Library

Spanish Romance

Christine Sterling was a white, wealthy socialite born in Oakland. Like many others of her time, she was lured to Los Angeles by promotional literature selling an idealized version of Southern California which emphasized its Spanish history: “The booklets and folders I read about Los Angeles were painted in colors of Spanish-Mexican romance,” she recalled in her journals. “They were appealing with old missions, palm trees, sunshine and the ‘click of the castanets.’”

In reality, L.A.’s Spanish history was only one piece of the puzzle: the indigenous Gabrielino-Tongva people farmed land in the Los Angeles Basin for thousands of years before—as part of the expansion of the vast Spanish empire that stretched across the Americas all the way to Argentina—the Spanish took the land from the Gabrielinos in 1781; Mexico won its independence after 400 years of Spanish colonization, and in the 1820s California became a territory of Mexico, renamed Alta California; and, in 1848, as per conditions of a treaty that ended the Mexican-American War, California was ceded to the United States.

In the 1880s, books like Helen Hunt Jackson’s Ramona and Land of Sunshine and Out West magazines popularized an image of California of the Spanish colonial era. That image was not only romanticized, but almost entirely fictional. The nostalgia for this period has been described as the “Mission Myth”: a belief that California’s missions were benevolent institutions that civilized the indigenous population. At the time of their operation, the Americans and Europeans who visited the missions often compared them to slavery, detailing their harsh and violent conditions. However, by the turn of the century this insight had vanished from the Anglo-American imagination, replaced by a picture of the Southwest as a lost paradise of simple rancho lifestyles.

So, it’s not surprising that when Christine Sterling encountered the historic heart of Los Angeles, she was aghast at how it had deteriorated. "Where," she asked, "was the romance of the past?”

Mary Pickford (center) and her co-stars from the 1910 film version of Ramona, Henry B. Walthall and Kate Bruce. Courtesy Mr. Harry Lechler, Piru. MVC Quarterly Volume 42, Number 3 & 4., 1998.

Legacy

Christine Sterling’s crusade to save the Avila Adobe was very tied to the notions of a “romantic” Spanish past—ideas that not only ignored indigenous history and culture but erased the trauma that accompanied centuries of European colonization. And, as Olvera Street attracted tourists from all over the country starting in the 1930s, the colorful papel picado and smiling Mexican merchants also masked the darker reality of the era’s forced “repatriations,” as the Mexican residents of Los Angeles, many of whom lived in that very same neighborhood, were coerced into leaving the United States. In the following decades, the “Mission Myth” images grew to dominate the idea of southern California. Mission Revival-style architecture, known for adobe bricks and tile roofs, can still be found in seemingly unassuming places (like the facade of Taco Bells).

Christine herself is a controversial figure. She was patronizing, and ruled Olvera Street with an iron fist. But, her legacy is also complicated: she provided real economic assistance and opportunity to the families who ran the puestos and the taquerias, at a time when LA was refusing to assist Mexican workers at all. Many of these businesses are still run by members of the same families today, and see Sterling as someone who gave them the chance to build their American dream when no one else would. Olvera Street attracts almost two million visitors every year.

Taco Bell facade. Rolando Pujo, 2014

Want to Learn More?

El Pueblo: The Historic Heart of Los Angeles. Jean Bruce Poole, Tewy Ball. The Getty Conservation Institute and the J. Paul

Picture This: California’s Perspectives on American History. Ramona and the Mission Myth. Oakland Museum of California.

California Vieja: Culture and Memory in a Modern American Place, by Phoebe S. Kropp

The Mythmakers’ Fandango: H. H. Jackson, Antonio Coronel, and Ramona Memories. PBS.