El Salvador’s Early History: Coffee and Conflict

Map of El Salvador, Rei Artur CC BY-SA 3.0 DEED

El Salvador

As we hear in Coffee Country, El Salvador is a country whose two centuries of independence have been profoundly shaped by both coffee and conflict. The smallest country in Central America, El Salvador is bordered on the north by Honduras and Guatemala, and cradled by the Pacific Ocean to the south. 6.5 million people live in El Salvador, with a quarter residing in the capital, San Salvador.

Poverty and violence – often perpetuated by El Salvador’s coffee oligarchy – have helped fuel modern Salvadoran migration to the US. Today, 1.5 million Salvadorans live in the United States and the Salvadoran diaspora sends back $7.5 billion in remittances every year. This amounts to over 25% of the country’s GDP. But Salvadoran migration to the US has a long history, closely entwined with the country’s troubled history as a coffee producer, and the violent civil war its inequalities helped to spark.

19th Century: the Fourteen Families

1821: Independence

El Salvador gains independence from Spain, after 300 years of Colonial rule, initially as part of the Federal Republic of Central America. Wealthy Salvadoran families continue to control power and patronage, especially after attempts to build a pan-Central American state fail (primarily due to in-fighting between elites), and El Salvador declares itself an independent Republic in 1841.

1846: The Birth of the Coffee Economy

In an effort to securely establish the young country’s future through planned economic development, the Salvadoran government backs coffee for the first time. The state offers tax breaks to anyone who planted more than 5,000 trees and exempts workers employed on coffee plantations from national military service.

Volcanic highlands of El Salvador, Volcan Izalco from Volcan Santa Ana, Rei Artur Credit: Ogwen, CC BY-SA 3.0 DEED

1860s: Expansion and Exploitation

Since the arrival of the Spanish in the early sixteenth century, a small group of people have maintained control over El Salvador’s most important natural resource: its land. This economically and politically powerful class, known as the “fourteen families,” form El Salvador’s oligarchy, wielding almost total control over El Salvador’s governance. Through the 1860s and 1870s, as profits from coffee production continue to increase, the acreage dedicated to coffee planation does too, with more than three million coffee trees growing in the fertile western highlands region around the Santa Ana Volcano.

However, much of the remaining land is communally farmed by Indigenous and peasant farmers, who continue to produce subsistence crops. This is seen as a major obstacle by ambitious coffee families, who want to expand their holdings.

1882: Land is Privatized

El Salvador abolishes the system of communal land ownership by a legislative decree. Farmers can now pay a fee to secure a title for their plot – or else the land is put up for auction. This process stretches on for decades, transitioning access to land, once seen as a social right, into a market commodity. Many indigenous communities lose access to their holdings, and must either work on the new coffee farms or move to the margins.

James Hill is among the oligarchs who establish a Santa Ana plantation. An Englishman who had escaped the Manchester slums, Hill arrived in El Salvador in 1871. He now sets about removing any non-coffee plant from his holdings, in order to ensure that his indigenous workforce could not feed themselves from the land, so would be dependent upon coffee wages.

In the same year, Austin and Rueben Hills (unrelated to James Hill) open “Arabian Coffee & Spice Mills” on Fourth Street in San Francisco. By 1906, this business would become “Hills Bros Coffee”, a major U.S. coffee importer operating out of San Francisco.

Women and girl making tortillas in El Salvador, c.1910. Credit: National Geographic, public domain.

20th Century: A San Francisco Story

1890s: An Industry Shift

As world coffee prices reach a historic high, Hills Bros. introduces the concept of “cup tastings” to the coffee industry, and begins to test imported coffee beans for taste and smell “in the cup”, rather than purchasing (and selling) coffee based solely on the beans’ appearance.

Grown in the rich volcanic soil and high altitudes of Santa Ana, El Salvador’s coffee beans are characterized by their balanced, honey-like sweetness and gentle acidity. Hills Bros “cup tastings” create a perfect market niche for El Salvador’s expensive, high quality beans.

By the end of the 19th century, Coffee has become El Salvador’s leading export, known colloquially as “el Grano de Oro”—the “grain of gold.” The intensive labor needed to grow and harvest coffee crops is supplied by hungry peasants dependent upon the minuscule wages paid by the oligarchs to feed their families.

1926: Peak Coffee

Hill Bros builds their coffee roasting plant at 2 Harrison Street at the Embarcadero in San Francisco.

The city’s coffee industry had grown exponentially in the past decade: wanting to maintain its own position in the transport industry, Pacific Mail has offered to transport Salvadoran coffee to San Francisco roasters for free, paying Central American growers directly in order to control their shipments. By the end of WWI, San Francisco merchants were buying a million bags of Central American coffee a year, five times more than a decade earlier.

By the 1920s, coffee is San Francisco’s largest industry.

Hills Bros Coffee opened its headquarters on the San Francisco Embarcadero in 1926. The HQ was closed in the 1990s, and the office block is now occupied by Tech companies including Mozilla, but the illuminated sign is still visible today. Credit: Dale Cruse, CC BY 2.0 DEED Attribution 2.0 Generic

Credit: The History Trust of South Australian, South Australian Government

1930s: Revolt, Repression and the Red Can

1932: La Matanza

In the 1920s and 30s, coffee alone represents 90 percent of El Salvador’s exports. But the heavy reliance on coffee causes economic disaster when the price in the international market falls 62% between 1928 and 1932. To recoup some of their losses, ruling families take over more land from Salvadoran peasants, and cut their workers' wages in half.

In 1932, labor leader Augustín Farabundo Martí led the farmworkers in a popular revolt, demanding better living and working conditions. The Salvadoran government responds by executing the revolt’s leaders – Farabundo Marti becomes a folk hero – and massacring an estimated 30,000 peasants in deliberate and planned shootings intended to strike fear into Salvador’s workers and erase the indigenous population. These events are known as La Matanza: the massacre.

The events of 1932 — almost completely unreported at the time – help set the stage for Hills Bros to dominate the U.S. coffee industry. Working with the country’s military dictatorship, Salvadoran planters increase production, selling more coffee in order to offset the collapse of prices caused by the Great Depression. Hill Bros. rises to the top of the U.S. coffee market, distinguishing itself from other companies like Folgers and MJB by almost exclusively buying low-cost, high-quality Salvadoran beans – produced by terrorized survivors of the massacre.

La Mantanza demonstrates to El Salvador’s land-owning elite the value of military dictatorship: Martínez’s regime is the first of a succession of military governments that control the country through 1979.

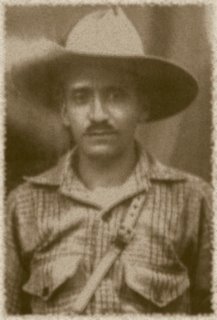

Portrait of Revolutionary Salvadoran leader Farabundo Martí. Martí was a leader of El Salvador’s Communist Party. After President Hernandez Martinez cancelled the results of elections held in January 1932, he helped to organize an uprising that saw Communist militia seize control of several towns in Western El Salvador, only for the revolution to be brutally crushed by government forces. Martí was arrested and executed. Tens of thousands of peasants were also murdered in the reprisal killings that became known as La Matanza. Public Domain

1939: Golden Gate International Exhibition

As we see in Coffee Country, in 1939 San Francisco hosted the Golden Gate International Exhibition, a tourism initiative that would draw over 17 million visitors over two years to the newly created Treasure Island. Among the amenities were carnival rides, concessions, art installations, live performances – and a Hills Bros. Exposition Theater showing “Behind the Cup,” a promotional film in Cinecolor which spliced together romantic scenes of the coffee harvest in Santa Ana with footage from the Hills Bros. factory in San Francisco. The film paints an innocent picture of the way coffee traveled through hands and across borders, conveniently omitting the more violent truth integral to the famous “Red Can” product’s domination of the U.S. coffee market.

Although links between El Salvador and San Francisco were weakened in the 1940s and 1950s by shifts in the coffee trade and the advent of air travel (which allowed wealthy Salvadorans to more easily reach other parts of the U.S. – many settled in Miami), the Salvadoran coffee trade remained an important part of the city’s economy through these decade – though its human cost remained largely invisible to incurious American consumers.

This pamphlet was handed out to audiences at the Exposition Theater.

Market Place in Santa Tecla, El Salvador, c.1932 Credit: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Collections.

Hills Bros “Red Can” coffee became an iconic symbol and an American household staple in the 1930s. Credit: Roadside Pictures, CC by 2.0 ND

Want to Learn More?

Coffeeland, Augustine Sedgewick

Hills Bros. Coffee—The Fulcrum Connecting San Francisco and El Salvador, FoundSF

Jan. 22, 1932: La Matanza (“The Massacre”) Begins in El Salvador, Zinn Education Project