The Undocumented Movement

Today, millions of people in the US live under the threat of deportation. They fear being separated from their families and communities, or being expelled to a country that—in cases like Ni de Aqui narrator Karla Estrada’s—had never really been home. Moreover, their rights and privileges in the US are often severely limited. As an eager and high achieving student, Karla was told by her high school counselor that, because she was undocumented, she should give up applying to college; she wouldn't be eligible for financial aid. Instead of giving up, Karla—and many other undocumented young people across the country—pushed for inclusion and a pathway to citizenship.

The DREAM Act

Until the 2000s, most undocumented immigrants avoided direct political action; it was too risky. But, when undocumented youth, who had been raised and educated in the US, began to apply for drivers’ licenses, work permits, and college educations, they were surprised to discover that their legal status denied them these opportunities.

They sought help from lawmakers and immigrant rights groups. In 2001 Senators Dick Durbin and Orrin Hatch responded, introducing the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act, a.k.a. the DREAM Act, to Congress.

The legislation would allow thousands of undocumented immigrants who entered the country illegally before they turned 16, and had since graduated high school—dubbed “Dreamers”-–to apply for conditional US residency, and be up for permanent residency after six years. Initially, it had bipartisan support. But 9/11 happened soon after the bill was introduced, and progressive immigration legislation—including the DREAM Act—was tabled. Multiple versions of the bill have been reintroduced in Congress since, but consistently fail to pass.

After the initial failure of the DREAM Act, undocumented youth began direct-action campaigns to push the bill through Congress. They organized marches, demonstrations, sit-ins in elected officials’ offices, fasting campaigns, and walkouts to rally support for their cause. Actions occurred all over the country, led by undocumented youth who were putting their entire lives on the line—borrowing from LGBTQ+ organizing, they “came out of the shadows,” and many revealed their undocumented status publicly as a part of these campaigns.

This new generation of activists emphasized their “Americanness” as part of their strategy. They wore high school graduation robes to marches, and portrayed themselves as high-achieving, English-speaking students raised on the American Dream. While anti-immigration sentiment still ran high in the decade post-9/11, public opinion swung in favor of the Dreamers.

Even still, after nine years of organizing for a path to citizenship, Congress failed to pass the DREAM Act by five votes. Suddenly, all the youth and students who had stepped forward were at an even greater risk of deportation.

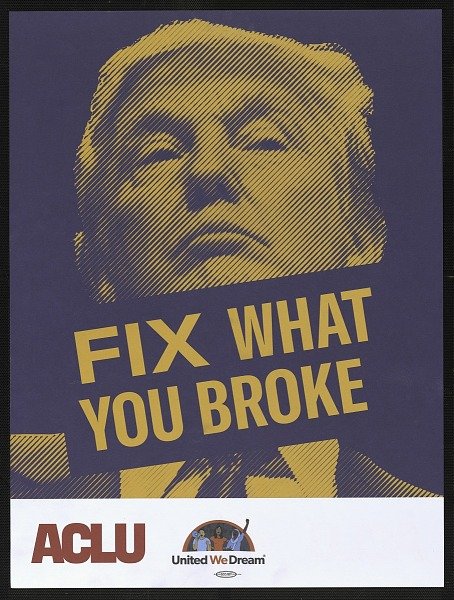

A poster used in the DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) protest on March 5, 2018; the day DACA was supposed to have ended. By Fairey, Shepard. Courtesy of Smithsonian National Museum of American History. 2018.0073.11

Organizing for DACA

In the wake of the DREAM Act’s failure, immigrant rights groups rebounded. A legal team looked into an obscure precedent called “deferred action,” through which presidents could protect immigrants from deportation on a case-by-case basis. What if this could be applied broadly?

After years of pressure from activists, former President Obama took executive action to announce the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. It allowed Dreamers to apply for renewable, two-year work permits. It also allowed recipients to get driver’s licenses, attend public universities, and apply for financial aid. Unlike the DREAM Act, DACA didn’t offer a path to citizenship. Still, a group of young people without voting rights or citizenship had taken on the US legal system—and achieved a huge victory. By 2017, around 800,000 undocumented young people had received deportation relief under DACA. Immigrants born in Mexico made up the largest proportion of recipients.

“The Ground Falling Away”

On a September day in 2017, Ni de Aqui narrator Karla Estrada was hanging out with her friends on Olvera Street. She was window shopping between two of the colorful puestos when she got an alert on her phone: Trump had rescinded DACA. Because Karla had arrived in the US from Mexico with her parents when she was five years old, DACA had protected her from deportation, and made her eligible for a renewal two-year work permit.

“I remember feeling like the ground had fallen away beneath my feet. The panic for my safety, and especially my family’s haunted me. I could not breathe. Tears fell from my eyes.”---Karla Estrada

Donald Trump campaigned on ending DACA, even though he did sometimes sympathize with the DREAMers. But, once in office, his Attorney General Jeff Sessions argued that DACA was illegal and such a large group could not live outside the reach immigration law.

When the news reached devastated DREAMers like Karla all over the country, advocates immediately sued. It went to the Supreme Court, and, in 2020, by a vote of 5-4, it was ruled that the Trump administration had acted improperly in terminating the program. The ruling means that the DACA program would remain in place.

A poster used in the DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) protest on March 5, 2018; the day DACA was supposed to have ended. By American Civil Liberties Union. Courtesy of Smithsonian National Museum of American History. 2018.0073.04

The Fight Continues

In 2022, the Biden Administration formalized the DACA program, which previously operated on a 2012 memo. But, ongoing litigation could keep DACA closed to new applicants and possibly lead to an end to the program. The whiplash between the Trump administration rescinding DACA and the Supreme Court’s decision—and the uncertainty of the program under Biden—is familiar to undocumented immigrants. For the past 20 years, they have faced unrelenting challenges to secure legal rights.

The undocumented movement is made up of an incredibly diverse group of activists. DACA and the DREAM Act only scratch the surface of larger issues facing their communities: undocumented activists today are organizing to change national policies around deportation, mass incarceration, anti-Black violence, inequality, reproductive health, and more. Moreover, the undocumented movement has sparked a national conversation about exclusion and the nature of belonging.

“Ni de Aqui” narrator Karla Estrada speaking at a rally for immigrant protections against deportation. (Andrea Castillo / Los Angeles Times)